Turkey

Turkey

Last updated: January 2023

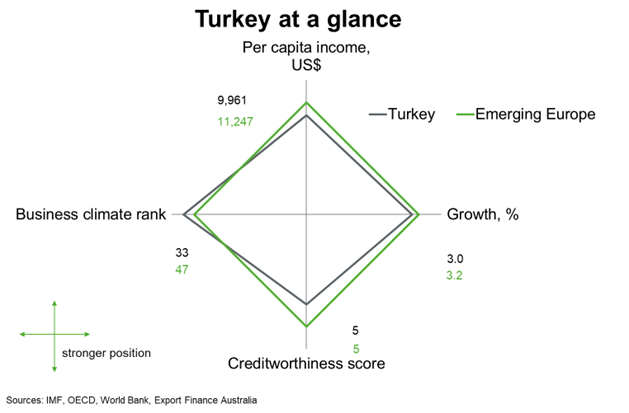

Turkey performs in line with emerging European countries on measures of creditworthiness, per capita incomes, growth and business climate. Growth has remained weak in the past few years in the face of political instability, an ongoing currency crisis and external financing pressure exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The above chart is a cobweb diagram showing how a country measures up on four important dimensions of economic performance—per capita income, annual GDP growth, business climate rank and creditworthiness. Per capita income is in current US dollars. Annual GDP growth is the five-year average forecast between 2023 and 2027. Business climate is measured by the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business ranking of 190 countries. Creditworthiness attempts to measure a country's ability to honour its external debt obligations and is measured by its OECD country credit risk rating. The chart shows not only how a country performs on the four dimensions, but how it measures up against other countries in the region.

Economic outlook

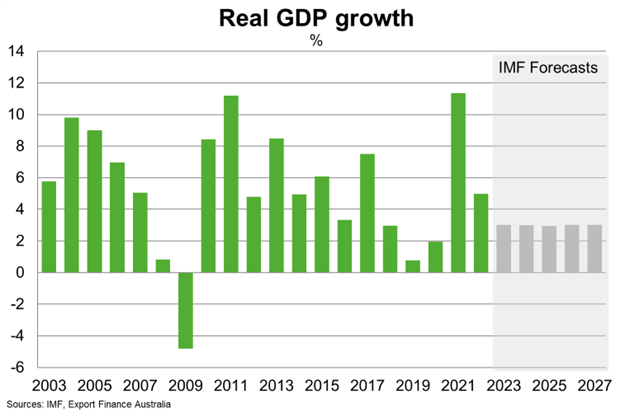

Economic growth fell to 5.3% in 2022 from 11.4% in 2021, as depreciation in the Turkish lira and soaring inflation (of more than 64% year-over-year in December) dampened consumer spending and investment. Exports grew strongly in 2022 on the back of the weaker lira boosting price competitiveness and increased exports to Russia (Turkey has not applied trade sanctions against Russia).

The February earthquakes caused significant damage to lives and property. The overall impact on GDP will be modest, but rising government spending and imports to support reconstruction efforts will increase the fiscal and trade deficits and add to inflation pressures. Prior to the earthquakes, the OECD expected inflation to remain above 40% in 2023, eroding household purchasing power. Turkey’s commitment to maintaining low-interest rates and the 55% increase in the minimum wage for 2023 (boosting incomes for about 30% of Turkey’s workforce) will support domestic consumption and broader economic activity. But weaker fiscal and external finances, and looser monetary policy, will add further downward pressure on the lira, which has fallen more than 20% over the past year. Weaker external demand and persistent geopolitical uncertainties will weigh on investment and limit export growth. Overall, prior to the quakes, the IMF projected growth to moderate to around 3% per annum between 2023 to 2027.

Risks to the outlook are high and tilted to the downside. The February earthquakes could take a larger human and economic toll. Large external financing needs and low reserve buffers leave the economy vulnerable to shocks. Further currency depreciation remains a significant risk, given it adds to Turkey’s large external debt burden and debt servicing costs. A still-high unemployment rate remains a risk to household incomes and consumption. An even sharper downturn in the global economy that weighs on Turkey’s major trading partners would hurt exports more than expected.

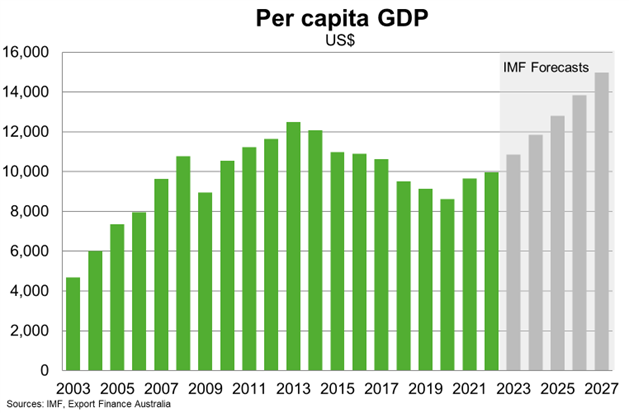

GDP per capita has steadily risen since 2019 on the back of significant increases in the minimum wage. Despite recovery in GDP growth and labour markets since the onset of the pandemic, the IMF expects the poverty rate to remain above pre-2019 levels because high inflation is squeezing budgets of lower-income households. GDP per capita is unlikely to reach the highs of 2012 until at least 2025, according to IMF forecasts.

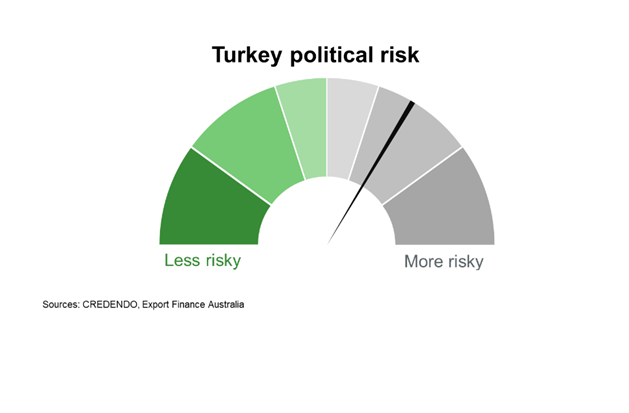

Country risk

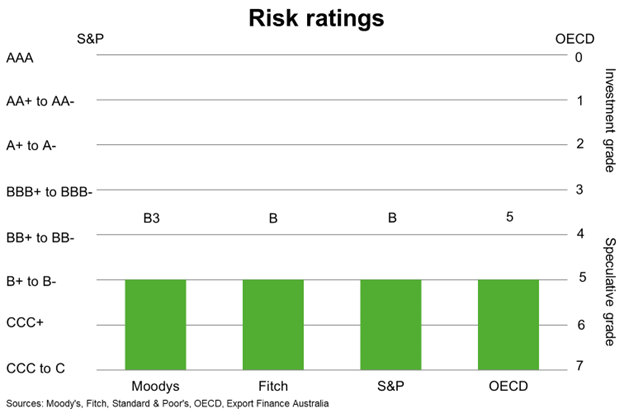

Country risk in Turkey is moderate to high. The OECD country grade is 5. This is akin to a sub-investment grade rating which implies a moderate likelihood that Turkey will be unable/unwilling to meet its external debt obligations. Turkey’s credit ratings have been lowered in recent years, reflecting the country’s weak external finances and ongoing political and policy uncertainty that have raised the risk of a balance of payments crisis and government default.

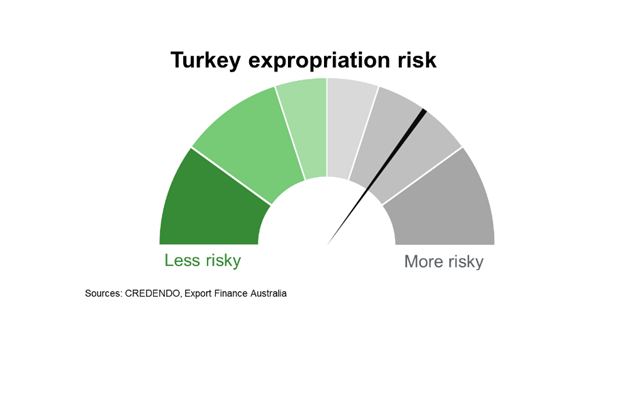

The risk of expropriation in Turkey is high. Since July 2016, the Turkish government has expropriated more than 1,100 companies worth more than US$11 billion. This is mainly because of companies’ alleged links to terrorist organisations.

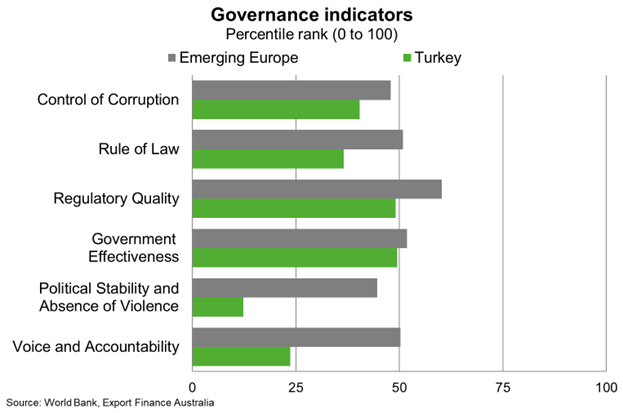

Turkey’s scores on several measures in Worldwide governance indicators are broadly in line with emerging European countries. But Turkey scores particularly lowly on measures of voice and accountability and political stability and absence of violence. Its low ranking probably reflects power struggles and constitutional crises that have occurred over the past 20 years and deep-rooted political, religious and social divisions. Ahead of May’s Presidential and Parliamentary elections, the risk of political violence and instability is elevated.

Bilateral relations

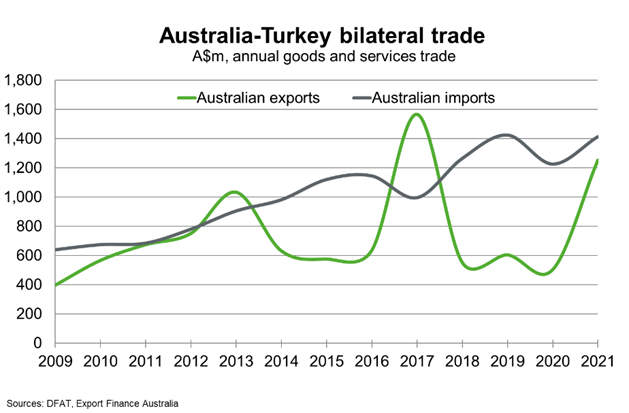

Turkey was Australia’s 34th largest trading partner in 2021. Total goods and services trade amounted to around $2.6 billion in 2021, more than $900 million higher than in 2020. Coal, cotton, and medicine were Australia’s chief exports to Turkey in 2021. Goods vehicles, fruit, nuts and limes and cement and construction materials were Australia’s main goods imports.

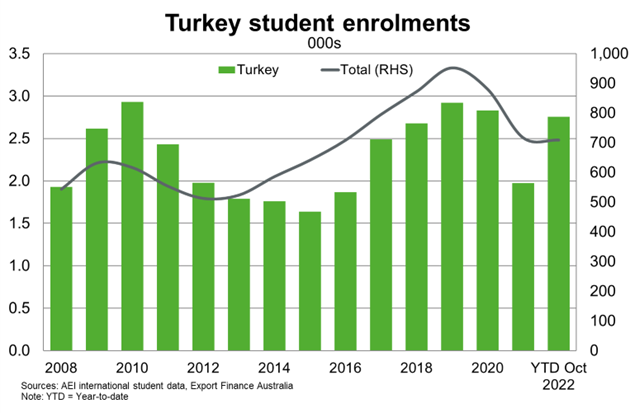

Remote learning supported Turkey student enrolments in Australian institutions through the pandemic, a trend that continued in 2022. Another year of open international borders should support further recovery in broader services exports in 2023.

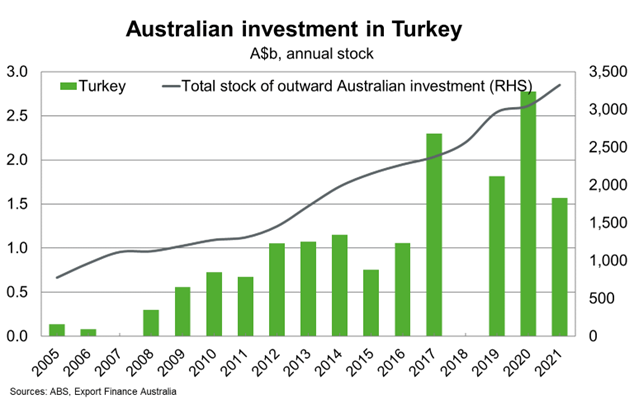

Bilateral investment between Turkey and Australia is modest. Australian companies have invested in Turkey’s infrastructure, mining, construction services, agri-business, and digital services. Turkish investment in Australia is very small.

Useful links

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Austrade