Southeast Asia—Variants and lagging vaccinations frustrate recovery

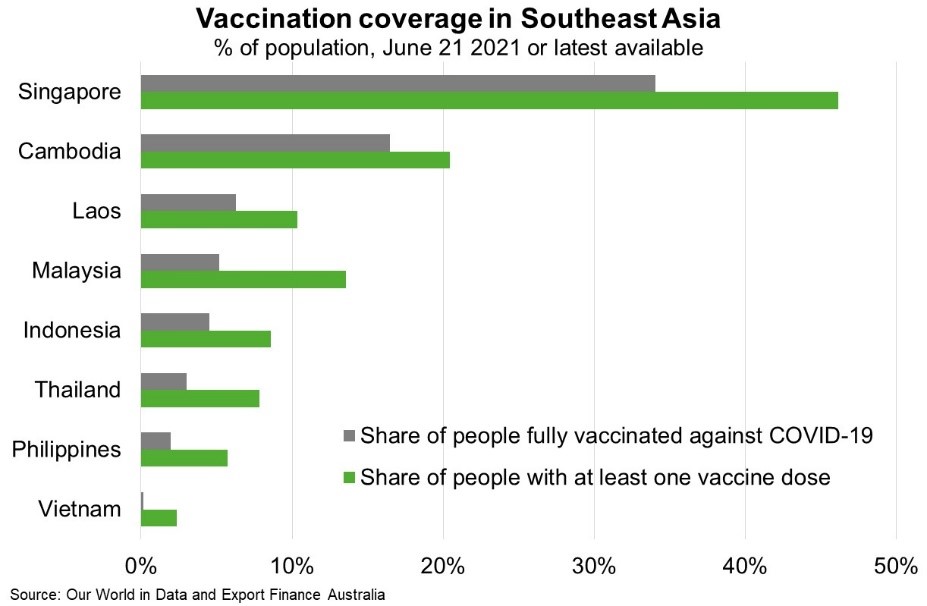

Many Southeast Asian countries once at the forefront of efforts to contain the COVID-19 virus are now battling new waves of infections including from highly contagious variants. Indonesia remains the most severely COVID-19 affected country in Southeast Asia, with record daily cases reported this month. National vaccination rates remain low throughout Indonesia and the rest of Southeast Asia, bar Singapore (Chart). The city-state is on track to achieve widespread vaccination by early 2022, with Vietnam set to closely follow. However, most of the region are unlikely to reach a similar stage of vaccination until late 2022 or into 2023. This owes to vaccine shortages and delays in delivering doses, bureaucratic and funding constraints, large and dispersed populations, and pockets of vaccine hesitancy, including due to doubts about the efficacy and safety of different vaccines.

Many of Southeast Asia’s powerhouse economies—Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia—saw economic activity contract in the first quarter of 2021. Tighter mobility restrictions will inevitably dampen second quarter results. Malaysia has instituted a temporary nationwide lockdown in response to record inflections at end-May, while some Vietnamese industrial parks have been closed due to localised outbreaks. Indonesia has also instituted 'micro-scale community activity restrictions’ but is facing increasing pressure to transition to a larger-scale lockdown.

Looking forward, the economic outlook depends on suppressing new variants until widespread vaccination is achieved. As mostly high-income countries race ahead with vaccinations and reduce distancing measures, the region may lag in the emerging two-speed pandemic. The recovery is likely to be uneven within the region. Economies plugged into global manufacturing and trade—Vietnam, Malaysia and Singapore—will continue to outperform. The diversification of manufacturing has seen Southeast Asia benefit from surging demand for medical supplies and IT goods. However, economies reliant on hard-hit services—like the Philippines and Thailand—will lag.