Emerging markets—Australia’s major export markets slow, as risks rise

The IMF expects real GDP growth in emerging markets (EMs) to decline to 3.7% in 2022 and 2023, down from 6.6% in 2021. EMs are disproportionately impacted by higher domestic and US interest rates, rising food and energy prices and growth scarring from the COVID-19 pandemic. Global efforts to decarbonise will hit EM producers of carbon-intensive products particularly hard, while surging inflation poses an increasing threat to political and social stability. As risks rise, weaker public finances in the wake of the pandemic leave many EMs with limited space to stimulate economies.

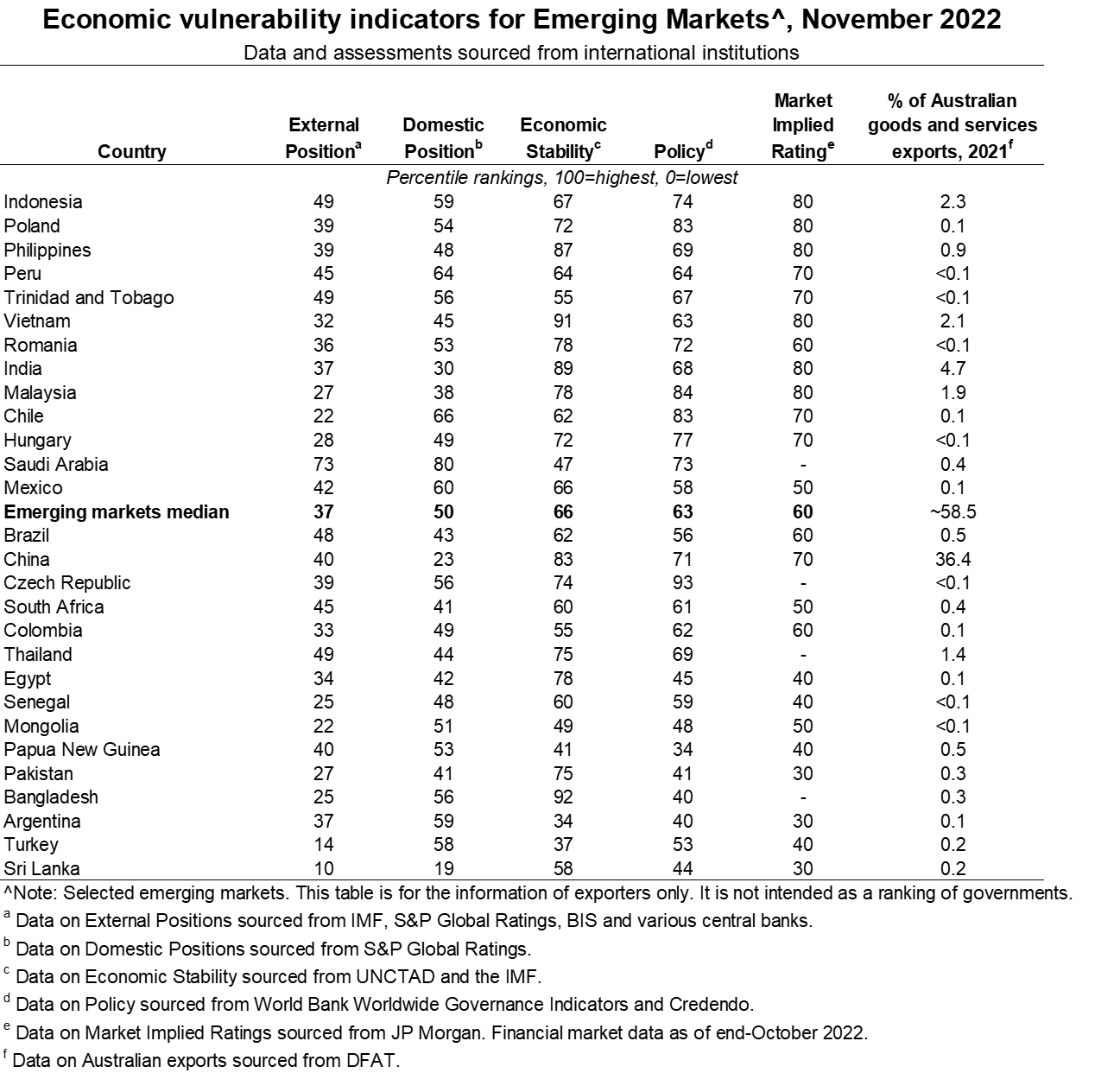

International institutions and financial market analysts, including the IMF, World Bank and S&P Global Ratings, use a range of indicators to assess the EMs most exposed to these risks.

- External position—what is the external debt and reserves position? Is the current account in deficit and how far has the currency deviated from its long term average?

- Domestic position—how leveraged is the private and public sector?

- Economic stability—what is the growth and inflation outlook? How reliant is the country on commodity exports, given the volatility in global commodity prices?

- Policy effectiveness—how effective is the regulatory environment and how severe are political risks?

- Market implied ratings—what do market risk premiums on foreign currency denominated bonds imply about market risk appetite?

Based on these indicators, many of Australia’s major Asian emerging export markets—such as Indonesia, Philippines, India, Malaysia and Vietnam—are less exposed. This reflects a relatively strong growth outlook, lower debt levels, robust external buffers, effective macroeconomic policymaking and improving governance. Saudi Arabia’s strong economic and fiscal outlook and efforts to improve the regulatory and business climate leave it well placed to handle downside risks. Chile’s vulnerabilities remain low overall, but stalling growth, high inflation and demands for higher social spending are compounding risks related to the business environment from the redrafting of the country’s pro-market constitution.

China and Thailand have capacity to withstand further global economic and financial volatility, but there are pockets of vulnerability in each country—for instance, China’s property market downturn and Thailand’s exposure to subdued international tourism.

Current economic and financial turmoil, alongside very high inflation, in Sri Lanka, Turkey, Pakistan and Argentina leave these countries more exposed to further global economic weakness, tightening financing conditions, and political and social tensions. Despite higher commodity prices boosting PNG’s economy, public finances, and prospects for a period of political and policy stability, buffers remain weak. Mongolia is also highly exposed to the global slowdown and tighter global financing conditions.