Colombia—Civil unrest as pandemic accentuates social discontent

Protests in Colombia in April were initially triggered by tax reforms needed to trim the government’s ballooning budget deficit. The bill has since been withdrawn and the Finance Minister has resigned. Nonetheless, violent confrontations have entered their fourth week, reflecting broader social discontent which surged across Latin America in 2019, since exacerbated by the pandemic. Colombians have endured one of the world’s longest lockdowns, which saw 2.8 million people succumb to extreme poverty last year. Protester’s grievances include planned health and pension reforms, high inequality and unemployment, and claims of human rights violations by law enforcement. A standstill in the streets has frustrated the distribution of basic goods, including food and medicine. The social crisis could see leftist presidential candidate Gustavo Petro win elections next year, while weaker reform prospects and unrest could jeopardise Colombia’s investment-grade credit rating. Exports to Australia’s second largest Latin American market will likely be challenged by the domestic crisis and border restrictions, particularly given the relative importance of services exports.

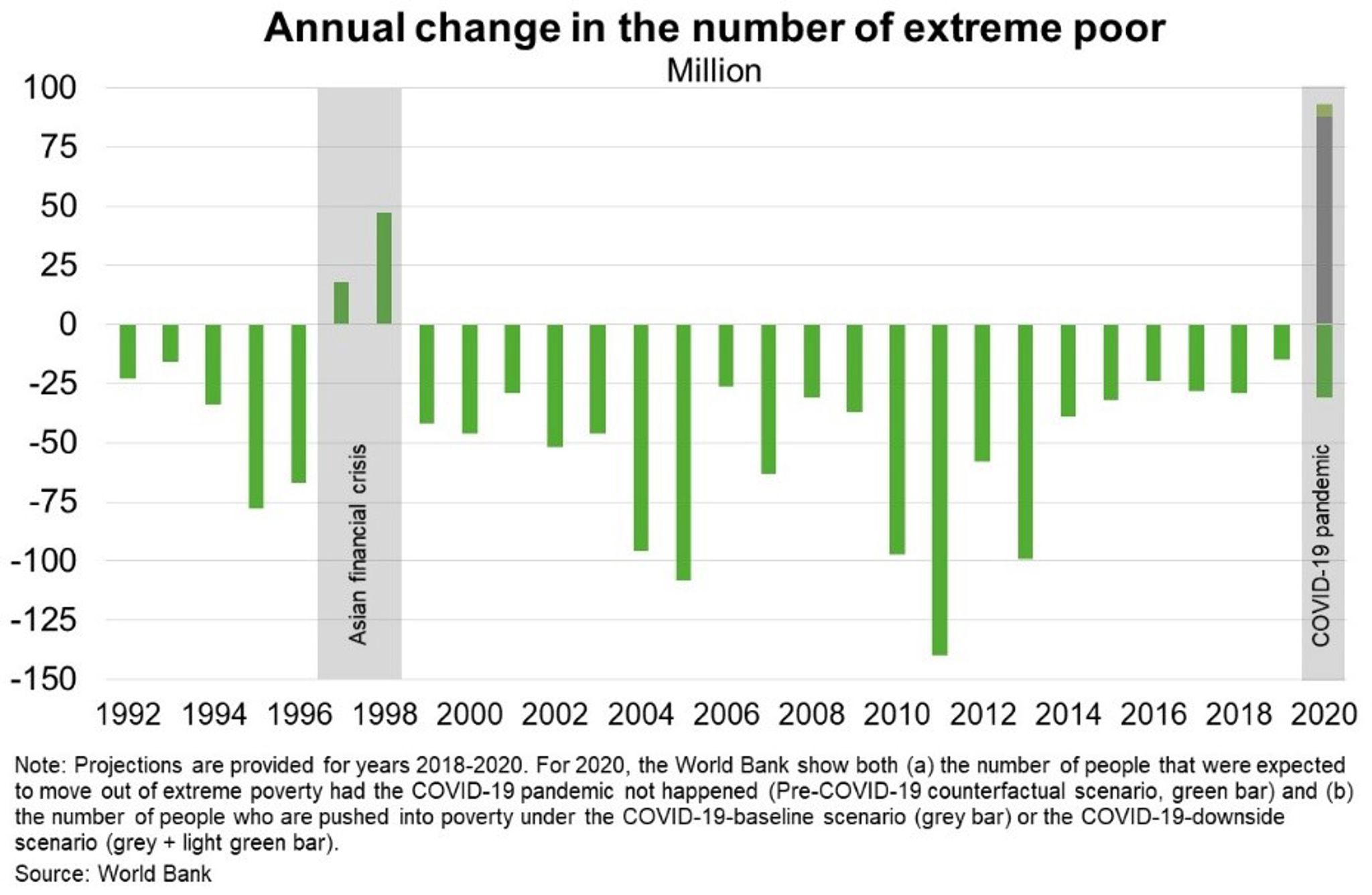

History is littered with examples of disease outbreaks causing social unrest. Epidemics can aggravate pre-existing societal fault lines—such as insufficient social safety nets, weak institutions, and incompetent or corrupt governments. Historically, epidemics have also triggered ethnic and religious backlash and worsened tensions among socioeconomic classes. Indeed, IMF research confirms a positive relationship between social unrest and epidemics. Unrest initially falls; crises tend to impede communication and transport critical to organising large protests, public opinion may favour solidarity in times of duress, while incumbent regimes may consolidate power and suppress dissent. However, the risk of riots and anti-government protests rises over time. So far, the COVID-19 episode conforms to the historical pattern; major unrest events worldwide have fallen sharply. But given global backsliding on poverty (Chart) and inequality, social unrest may re-emerge in more countries as the pandemic eases.